|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

It was a damp and drizzly morning in a well-settled neighborhood

in Bangalore when Anita Reddy and her father Dwaraknath Reddy heard a knock on the door of their family home—a knock that

triggered a series of unexpected events and changed the course of their lives forever. Anita and her father opened the door

to find a lean and frail figure, stooped over, anxious for help. “Everyone in this city is turning a cold shoulder on us.

They think we are beggars. Please help us,” the old man said as he clutched his stomach with hunger and tears moistened his eyes.

Mr. Dwaraknath Reddy welcomed him into their home while his daughter, Anita, brought the man some food. As he ate his first real

meal in many days the old man, Purushottam, told them his story.

|

|

|

|

|

|

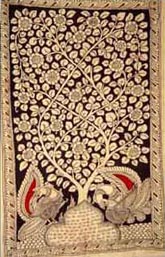

“I come from a large community of artists in Srikalahasthi and we paint kalamkari on cloth for a living” he explained, as he displayed one of his paintings

on the floor. The piece was an art panel, depicting “the tree of life” bursting with beauty from its

very roots; it is a symbol of peace, prosperity, and the vibrancy of life—yet ironically,

the creator of this exquisite painting, like hundreds of other kalamkari artists, knew only a

life of hunger, suffering and distress. “We come to big cities and go door to door trying to

sell our art, but more often than not, we are mistaken for beggars and driven away.” It seemed

tragic that a man so rich in talent and skill was forced into a life of starvation because he

was unable to sell his exquisite kalamkari paintings.

“Ours is a traditional skill passed on

from generation to generation, by our ancestors,” Purushottam said. He went on to explain

about kalamkari art to Mr.Dwaraknath Reddy and others in the family who had by then gathered

around him, eager to hear his story.

|

|

|

|

|

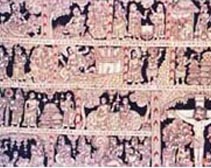

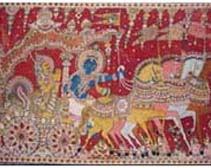

“We treat the cloth

with milk and then sketch on it by hand, using burnt tamarind twigs. Nimble

fingers of artists can transform blank cloth canvases into vibrantly colored

forms. Using vegetable dyes and earthy hues—pomegranate reds, leaf greens,

raven wing blacks and Lord Krishna blues—kalamkari artists create works of

splendid beauty. And yet, we are not able to sell these rich paintings. We

consider ourselves fortunate to return home with even a few hundred rupees.

We make barely enough to feed our families, and yet,

what choice do we have?” he asked in despair, turning his eyes towards

the heavens. “We continue to celebrate our traditions, our myths and

legends. We struggle, we strive, and we create art that speaks of

a vibrancy, of celebration, of tradition, and of our Gods—but our Gods

seem to have forsaken us and we are starving…” His voice trailed off,

not in anger or bitterness, but in absolute abandon of any hope.

|

|

|

|

|

Why was Purushottam

in such dire straits? The canvas of his life was frayed and tattered.

Although he was skilled in an art that gave shape to his imagination in

a myriad hues and he could draw exquisite lines that came alive in

spiritual paintings, he still needed food to satisfy his body. After

Purushottam finished his meal, he felt temporarily rejuvenated, both in

body and soul. He looked up once again at Anita and her father. They were

engrossed in conversation. He listened intently and heard them say “Let us

go to the village…tomorrow! Let us unite and organize the artists to make

a difference.” Purushottam listened to the words. A faint flicker of hope

glimmered in his eyes, and he held the promise of a better tomorrow. He

smiled at them and returned to his home.

|

|

|

|

|

|

The very next day,

Mr.Dwaraknath Reddy and his daughter Anita made their way to Srikalahasthi,

a small town in southern Andhra Pradesh, where they met again with Purushottam

to initiate a project to help kalamkari artists survive and thrive on their

artwork. In one circle, gathered together by the side of the dusty road

adjacent to Purushottam’s hut, 25 young women sat chattering away with

excited anticipation of a new future. They wanted to learn the traditions

of kalamkari and find a means to support their families. In another circle,

not far away from the young women, sat a group of male artists sharing

their thoughts on the possibilities of new support for their artistic

skills.

|

|

|

|

|

Anita and her

father found that in Srikalahasthi there were others, not just kalamkari

artists, who were shattered by poverty and misfortune, desperate for

sustainable markets in which to sell their wares. They met Dalit stone

cutters from the Enagaluru village, their skin parched by the scorching heat

and glare of quarry walls, and their hands and spirits roughened by the

toil of breaking stones. They met weavers who spoke of the mighty dept trap

that engulfed them all, and the physical disabilities and illnesses they

contracted through the strain of their detailed work. These weavers produce

some of the country’s finest cotton fabrics in their tiny huts—homes

barely large enough to accommodate their looms leave alone space for

their families! It was evident that all were caught in a web of debt

and desperation, shattered by poverty and misfortune. Yet one could

sense that many of these artists retained dreams and aspirations for

the future of their work and lives; Anita and her father could see

a faint glimmer of hope in the artists’ desperate eyes.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

DWARAKA was

born to fulfill these dreams and aspirations. Dwaraknath Reddy gave

the rural artisans his assurance that the Ramanarpanam Trust would support

a socio-economic empowerment program for them—a program in which the entire

village could learn to develop a market to provide sustainable support for

the rest of their lives; or as the proverbial saying goes: “to catch fish and

eat for a lifetime rather than to be given fish to eat for one day.”

The Ramanarpanam Trust has lived up to that promise. In the five years since its inception, hundreds

of artists and weavers have been impacted by the support of DWARAKA—just one of many Ramanarpanam

Trust initiatives. The support, in the last few years alone, runs into over Rs 4.5 to 5 million.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

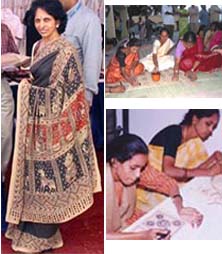

Fascinated by what

they had seen and heard from these young women working with DWARAKA,

Raji Narayan and R. Ramkrishnan, left in raptures. They decided to join

Anita and her friends Dharini and Gita in their endeavor, and—living by

the values of Dwaraknath Reddy and the Ramanarpanam Trust—the team nurtured

and guided the DWARAKA effort from the very beginning, enabling the artists

to stride along their road towards empowerment. While mobilizing the artists’

community was the most critical aspect of the empowerment process, there were

many other challenges that the DWARAKA team encountered and sought to

creatively overcome. The team realized the need to focus on the development

of efficient systems and infrastructure in the village, support emergency

medical needs and rebuild shelters, explore the infinite range of

possibilities for new kalamkari products, and help establish proper

marketing channels for these new products.

|

|

|

|

|

|

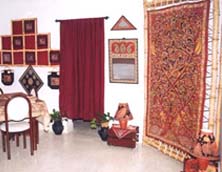

Another important

aspect of the economic empowerment effort was to set up a separate Community

Development Fund from the market sales, in addition to the regular earnings

of the artisans. The artists were mobilized into smaller groups to facilitate

operation of the Fund, each group maintaining his or her own bank account.

This fund is a blessing, especially for the women who have discovered in it

a new sense of economic independence. Before the emergence of DWARAKA,

the majority of kalamkari work took form in wall panels, which unfortunately

command a very limited and exhaustible market. DWARAKA worked to develop an

entirely new and exclusive dimension to kalamkari by designing a

comprehensive product range that caters to the needs of a global market.

Through these new kalamkari products the efforts of artists were sustained

and the scope for the art's survival was widened. Working in collaboration

with the DWARAKA team, especially through the guidance of Raji and Anita,

kalamkari artists began to see the many ways in which their work could be

transformed—into beautiful mirrors, sarees and dress material, cushion

covers, purses and handbags, greeting cards and a plethora of other

innovative and stylish products. The artist's enthusiasm resulted in

an overflow of new kalamkari designs, and the need to direct efforts

towards marketing these products arose, sending Ram, Raji and Anita into

a marketing frenzy! It was at this point that the DWARAKA Showroom—an

exclusive kalamkari boutique in Bangalore, the only one of its kind in

the whole country—was opened. In just three years the DWARAKA effort has

grown immensely, buttressed by the support of several non-profit organizations

and cultural platforms, and has gained national and international recognition

for the innovation and social empowerment that the team has worked to cultivate.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Below: Kanchana’s brother Srinivas, mother and two younger siblings.

|

|

A glance at the house next door to Purushottam’s and Anita felt deeply moved. A young girl sat outside spinning the “Charkha” wheel. It was hot and humid. Her mother and brother, sunk waist-deep into a pit were peddling away at the loom, weaving a most exquisite saree. What were the wages for their labour? A mere few hundred rupees, more debt and the potential for starvation. This was Kanchana’s family. Kanchana was desperate and asked Anita if she could learn Kalamkari. DWARAKA provided her the platform, and the rest is history. Today Kanchana’s success story would be an inspiration to many. A quiet, shy girl when she first joined DWARAKA, she blossomed into a self-confident and self-reliant young lady with a deep commitment to strive for improving her artistic skills, as she always works for perfection. The Ramanarpanam Trust supports others in her family, including her brother Sreenivas, a weaver, who was given Rs. 20,000 support to acquire a skill in the mobile phone repairing vocation, enabling him to earn additional money for his family.

|

|

|

|

Their father, Mr. Venkateshwarlu was one amongst many weavers in the Bhaskarpet area of Srikalahasthi who repaid a revolving fund grant of Rs. 10,000 given to each of them by the Trust. Kanchana at times earns Rs. 2,500 to Rs. 3,000 per month, doing exquisite Kalamkari paintings and is today a pillar of strength not only to her own family, but to the entire DWARAKA family.

|

|

|

|

|

|

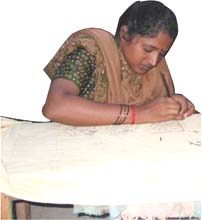

Sarasa Bai has been a pillar of strength in DWARAKA. Although from a poor family that has had to struggle to lead a decent lifestyle, she has been the embodiment of stoic resilience. Sarasa’s hard work has produced some of the most beautiful paintings and have helped her earn up to Rs. 2,500 to Rs.3,000 in a month. Ramanarpanam Trust helped Sarasa’s family with their shelter needs, and also reached out when they were desperate for support to cover medical expenses. Sarasa is a confident young woman today, capable of representing the DWARAKA artisans in National Exhibitions, and , like some of her other comrades has the potential to make a mark on the International scene as well.

|

|

|

|

|

Ganga was barely 15 years old when circumstances of poverty forced her to shoulder the responsibility of protecting and providing for her family’s needs. She stood tall in the face of adversity. She learned and excelled in painting Kalamkari. Like her, other friends who were trained in the art of Kalamkari by the DWARAKA team, Ganga too received a stipend of Rs. 300 for 2 months from the Ramanarpanam Trust during the training period. And now, when she is at her best, she earns up to Rs. 2000 and more per month, with which she has helped her family rebuild a new home for themselves. She even supports her sister through college. DWARAKA has indeed changed the way Ganga and her family live today.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

The two women stared vacantly with a resigned, distant look in their eyes. The older one, Ramachandriah’s wife had no desire to continue with life. Her only son committed suicide unable to bare the agony of their poverty. And now she was a mute witness, as her husband, too frail and weak to continue his work at the loom, collapsed and died. For Kavitha, about 18 years old, having lost her father and brother, the only two male earning members in the family, the responsibility of looking after her mother and herself, left her vulnerable and despondent.

Balakrishna’s daughter has also been strapped with the responsibility of spinning yarn and weaving cloth to support her ageing parents. These are but two of the many such cases in the weaving community of Sri Kalahasthi that have sought the help of the Ramanarpanam Trust. Reaching out to them in their hour of need, the Trust has helped them rebuild their meager dwellings, protect the looms and given them skills to sustain their livelihoods. With the help of the Ramanarpanam Trust, the tears are drying and the smiles are coming back.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Rekha needed an emergency medical intervention to save her life.

“What’s it all about?” Anita wondered, remembering the lyrics of a popular song she had once heard. Rekha, a young Kalamkari artist, was at Shimsha Hospital in Tirupati, near Srikalahasthi, when Anita went to visit her. There was an overwhelming feeling of the Divine presence as the two of them held each other, one giving much-needed succour, and the other accepting it. Rekha’s life had to be saved. She was 21 years old and diagnosed to have a critical heart condition. Only a

|

|

|

|

|

surgery could save her. She and her sister Padmavathi were both given stipends by the Ramanarpanam Trust to learn and practice Kalamkari.

Just as they seemed to be becoming self reliant, economically and socially, the tragedy of the illness came as a blow to the family. As she lay in bed in Shimsha Hospital at Tirupathi, in anxious preparedness for the surgery, Rekha was gripped with fear. Her poor family could not afford a heart operation.

It was nearing midnight, when Anita was leaving a meeting in Sri Kalahasti for her home in Bangalore. Keeping her promise to Rekha, Anita stopped to see her at the hospital –and, that’s how it all happened.

Bright and shining, outside Rekha’s window, Anita saw a rainbow of lights brightening the pilgrim’s path to the abode of “the Lord of the Seven Hills.” The lights, created a silhouette against the dark hills and the midnight skies were like a necklace of fire flies flying towards the heavens. There was a prayer in Rekha’s heart, and, there was a prayer in Anita’s heart. The moment was not without its share of fear. Tears gleamed in both their eyes. They were tears of love and hope. Suddenly both felt the Embrace of the Lord; felt that He had come down from the hills just to hold them, and in that moment, enveloped with a feeling of total surrender, Anita hugged Rekha.

The flame of hope shone bright. Rekha had her operation, and the Ramanarpanam Trust supported her. The operation was a success. Today she is happily married and

|

|

|

|

has a beautiful little girl, Vaishnavi. As days passed, her sister Padmavathi borrowed a loan to touch up and repair their dilapidated house, in which the entire family lives with their parents. She was economically empowered to stand on her own feet through the DWARAKA effort, was equipped to repay the loan—which she did—and proved that the poor can be very responsible with financial loans. The two sisters say, “it is DWARAKA and the Ramanarpanam Trust that have touched our lives to make a difference. We thank Appa for his kindness. We live with a new hope now…”

|

Above: Rekha with her beautiful

daughter

Vaishnavi, and

sister Padmavati. |

|

|

| |

|

|